The Peak as the Pedastal

A lone chapter from an unwritten metaphorology on mountain-peaks.

In 1804, on a grand tour through Italy, a Bildungsreise, Friedrich Schinkel, the Prussian architect, writes about his ascent to Mount Etna: “It was as if I could see the entire world with a single gaze… Everything below was so easy to grasp that I felt myself to be greater than the world, outside of any relation.” To stand “outside of any relation”—solitude; that is also the core sentiment of Caspar David Friedrich’s famous and roughly contemporary “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog”; also of his even more fascinating “Monk by the Sea”. Goethe, speaking to Eckermann, mentions, in recounting his hikes to the Ettersberg mountain outside of Weimar, a very similar sense of subjective greatness: “I went up the mountain many times, and in these last years I thought, every time, that it would be last time I get to take up there such a lofty view of the world and its riches… In our own narrow houses we shrink. But on the peak we feel large and free, as nature is, the nature before our eyes, and this great feeling a man should, in the best case, always feel.” To the feeling of size, of greatness, Goethe relates the feeling of freedom, to be liberated from “narrow houses”. In Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell, the eponymous hero, when speaking of liberty, points to mountains in the distance.

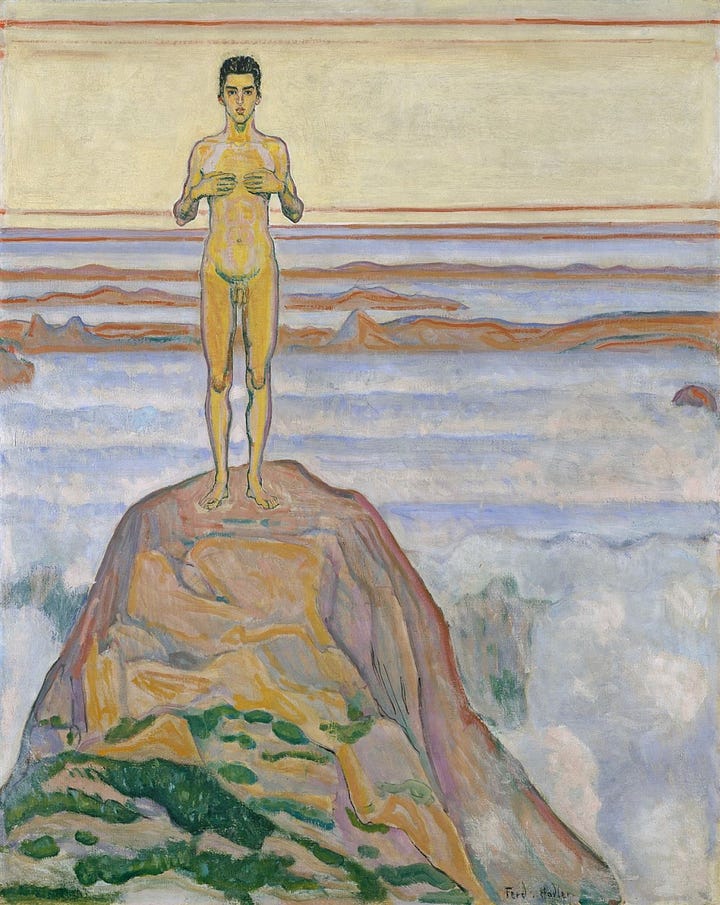

The Sattelzeit, the age between 1750 and 1850 in which modernity was born, strongly favoured, against the remnants of absolutist social convention and the onslaught of industrial society—both, in a Rousseauian sense, the “chains” of the free man— natural metaphors: the forest, the sea, the fields, etc. In 1798, the poet Brentano speaks of the dichotomy: To become a man—free, or to become a “bourgeois”—a pig; one precludes the other. Certainly, this romanticist sentiment springs from an elitist disposition, and it is the natural metaphor of the peak that becomes the elitist metaphor par excellence in this age, the most productive metaphor of the most productive men. To stand on the peak: to be taller, greater, to be free, to be alone—a spiritual experience: for to “discourse with creation”, quo romanticist dogma, solitude is required. Caspar David Friedrich writes: “I have to be alone, and I have to know that I am alone in order to feel nature fully, and to see it fully. I have to surrender myself to my surroundings, to unite myself with my clouds and my rocks, in order to be who I am.” The elitist sentiment of solitude rests on the sharp distinction, spatial and spiritual, between the “peaks” and the “lowlands” of mankind. At the same time, the “peak”, as a realm of remove, high up above the average cultural and social landscape, seemed to convey to the romanticists the sense that the laws of the “lowlands” no longer bound them; the peak as an elitist metaphor is thus also, necessarily, an “anti-social”, anti-conventional, egotistical metaphor. Total liberty, high up, where the eagle soars. The 18th century Alpine traveloguist H. R. Schinz writes: “In these dizzy heights I felt as if in a different world altogether, in which all the notions and impressions of social life, all these human affectations and the supposed comfort of domestic fortune had been swept away and exchanged for a barren, rough, but also sublime and great naturalness, one that instills in every thinking being a pleasant melancholy never felt before.” The art of the baroque, preceding the Sattelzeit, was an art of “social relevance”, always calculated for a specific public, often courtly, audience; the cardinal term of the baroque, of the ancien regime, is “sociability”, polemically-speaking a term of “domestication”. But the cardinal term of any kind of romanticism is “solitude”. The lonely artist, the lonely great man—and, increasingly, the lonely great man facing an overwhelming and yet confined cosmos. A sense of abandonment in a mighty, uncanny, threatening world—we see it in the works of Goya, Füssli, C.D. Friedrich. In Friedrich in particular this is radicalized to the point where his figures appear as if they might be the last people in the cosmos, against the cosmos. A similar sentiment we find already in a passage by the Geneva scholar Benedict de Saussure, who writes of his ascent to the Mont Blanc in 1787: “The silence, the deep quietness which governed these expanses around me, and which in my imagination appeared even more sizeable, instilled in me a great sense of dread. I felt as if I had survived a catastrophe and everything below me was but the world’s corpse.” Inspired by Mary Shelley’s apocalyptic novel “The Last Man”, the English painter John Martin left us a cycle of paintings on this frightening vision; in one of these paintings, high up on a mountain-peak, stands “the last man” akin to an old testament prophet above the ruins of the world, as the sun, in a red mist, motions to set below the horizon. The figure of the great man as an abandoned, tragic hero dwelling in or drawn to mountains we also find in the literature of the age. In MacPherson’s Ossian poems, or in Hölderlin’s play Empedokles we find the romantic “artist-seer” figure, clad in nordic-gaelic or in greek-mediterranean masks. Hölderlin’s Empedokles, the great and lonely priest-prophet, who dwells in a mystical union with nature, who alone understands the world’s secrets: In the end it is his contempt for the “lowliness” of mankind and of mankind’s convictions that see him ascent to the peak of Mount Etna—but before he surrenders himself to the vulcanic flames, he, who thought himself a god, rhapsodizes the peak: “For things are different than before! gone, gone are / My trials with human beings! as though / I’d grown strong pinions, with me all is well and airy / Up here above it all, and rich enough and glad enough / And splendidly I dwell here near the fiery chalice, / Filled with spirit to the brim and wreathed / With flowers he himself has cultivated / My father Etna offers me his hospitality. / And as the subterranean storm celebrates / By reaching to the cloudy precincts of / The blood-related Thunderer, flying heavenward / With joy my heart too flourishes; / With eagles here I sing the canticle of nature.” Likewise the Scottish hero Ossian, imitated ingeniously by MacPherson, declared by the pre-Romantics as the “ideal” of the epoch, dwelt in the wild solitude of the Scottish highlands. P. O. Runge illustrates Ossian as a giant, superhuman figure with harp, horn, winged helmet, “seated on the highest peak”. Even more expressively, Füssli, illustrating Thomas Gray’s poem “The Bard”, lets his bard dangle above an abyss. In certain elements similar to Hölderlin’s Empedokles is Byron’s Manfred, the nobleman (perhaps the Sicilian king?) who, digusted by life, seeks death in the mountains by throwing himself off an Alpine mountain-peak, the Jungfrau. The great man, Manfred, seeks his grave in the majestic solitude of the untouched, inaccessible nature of the mountain-range, never to be spoiled by men. He soliloquizes: “And thou fresh breaking Day! & you ye Mountains! / Why are ye beautiful? I cannot love ye. / And thou the bright Eye of the Universe / That openest over all—& unto all / Art a delight—thou shin’st not on my heart. / And you ye Crags! upon whose extreme edge / I stand, and on the torrents’ brink beneath / Behold the tall pines dwindled as to shrubs / In dizziness of distance—when a leap— / A stir—a motion—even a breath—would bring / My breast upon it’s rocky bosom’s bed / To rest forever—wherefore do I pause?” The Manfred-topos, just as Goethe’s Faust before it (Faust, too, ascends to the mountain for the sabbath of the witches), left a deep impression on romantic and post-romantic artists. Robert Schumann set Manfred to music, John Martin and Ford Madox Brown illustrated scenes from it, Stendhal uses quotations from it in the epitaphs for “The Red and the Black”. The figure of the abandoned man on the peak, who is, naturally, in the artist’s imagination also always an artist—: we began with the sense of superiority, of freedom, now we must add the willingness to die, suicide out of disgust, out of pride, as the ultimate elitist gesture, to our metaphorological complex. The peak—the great man—abandonment—solitude—pride—suicide. Brentano, who was referenced before, fittingly once said of himself that he had spent his entire life “on the peak of a mountain spitting on the commoners”; and it was Schelling who called Winckelmann a genius “so exalted in his solitude, like a mountain-range.” Perhaps another great example is what Camille Lemonnier says of Delacroix: “Alone atop his rock, high above the noise of the universe, his egotism is divine. Nobody should demand of him to descend to the zones of mankind.” It is the apotheosis of the great man to which the image, the metaphor of the peak gives an expression. Where once gods stood, on Olympus, the great man—the hero, the genius—now stands, cf. Goethe’s popular image as the “Olympian”, cf. Napoleon as Jupiter, cf. the “divine Beethoven”, perhaps the loneliest of all great composers, deaf, in the end, to the “noise of the universe”. As Übermenschen they pose above mortals; but also fall—like Empedokles, like Manfred—willingly, one imagines. It is not surprising that Nietzsche has Zarathustra start out atop a peak, and that to speak to men he has to descend. A final illustrative painting that comes to mind is Ferdinand Hodler’s recourse to this romantic metapherological complex in his “Gaze into Infinity”, from 1916. But Hodler’s figure no longer gazes out into an infinity also seen by the spectator, his back turned, as it was in Friedrich—no, Hodler’s even more modern man no longer knows the polarity between man and nature; instead, he looks directly at the spectator, into the spectator; but still alone on the peak, superior, judging. Do we rise to meet his gaze?